When you trade options, you can be either a buyer or a seller.

Each side has different rights and risks.

To explain in greater detail what these mean, we will look at 2 different analogies.

First analogy will help you understand what happens when you buy options.

Second analogy will help you understand what happens when you sell options.

How options work – “apartment buying reservation” point of view.

This is useful if you want to be a trader who buys options.

How options work – “insurance company” point of view.

This is useful if you want to be a trader who sells options.

How to look at options trading if you’re buying options (buy call example):

The Setup

You find a good neighborhood in a crowded city where the apartments are being built.

The apartment costs $300,000 right now.

The neighborhood is in development and it might get extremely good if it gets better traffic connection, or it might become bad if it stays isolated for a long time.

You see the potential and pay the owner of a building $5,000 to reserve the apartment for the next 90 days to see what are the plans for the neighborhood.

The owner of a building (the seller) agrees to keep the apartment for you in the next 90 days for the price of $300,000.

This means that for the next 90 days you can buy that apartment for $300,000, no matter what happens with the neighborhood.

Now, there are 3 scenarios that can happen:

1) news are bad – the neighborhood traffic will stay as it is and it will become a factory zone, isolated from the city.

Your locked price of $300K suddenly looks like a terrible deal.

- You don’t “exercise”: You simply don’t buy the apartment

- You lose: Your $5K premium (gone)

- You avoid: Buying at $300K when it’s worth $250K = avoiding a $50K mistake

Your maximum loss was $5K from day one. You knew the risk upfront.

2) news are great – the neighborhood gets additional traffic connections, parks, shops..

Your locked price of $300K is now worth a fortune.

- You exercise: Buy the apartment at your locked $300K price

- You now own: An apartment worth $400K

- Your profit: $400K – $300K – $5K (your fee) = $95K profit

You controlled a $300K asset by paying only $5K upfront.

3) Nothing new

A developer wants to buy the whole block. He speculates that the area is about to boom.

His offer: “I’ll pay you $15K for your right to buy that apartment at $300K.”

- You sell your reservation: $15K

- You never buy the apartment: You don’t need to. You just sell the option.

- Your profit: $15K – $5K (your original fee) = $10K profit

Congratulations – you made money without ever owning the apartment. You just controlled it for 30 days, then sold your control rights to someone else.

Let’s apply that way of looking at a trade on a chart:

If stock x is at $10 now,

- You buy an option which is cheaper ($1),

- Pick a price of $11 and give it time (30 days)

- You start profiting if it goes above $12 in the next 30 days.Your full profit is anything above $12 minus how much you paid for a bet – also called a premium.

Let’s recap:

1) Your loss is capped

- Max loss = $5K (your premium)

- NOT $50K if the market tanks

2) You control without owning

- For 90 days, nobody else can buy that apartment at $300K

- You have leverage: controlling a $300K asset with $5K

3) You identified a good opportunity before others but are not interested in actually owning what you reserved.

- You sell your reservation to someone else

- You pocket the profit without ever needing the apartment

- This is the most often scenario

This recap example explains how everything works if you’re betting on something to go up, the same rules apply if you were to bet on something to go down.

How to look at options trading if you’re selling options (sell a call example):

The Setup

You’re now the BUILDING OWNER (the seller), not the buyer.

You own an apartment building in that same neighborhood.

The apartment is currently worth $300,000.

You think: “The neighborhood will stay stable for the next 90 days. Nothing major will change. The value won’t spike.”

A buyer comes to you and says: “I think this neighborhood is about to boom. I’ll pay you $5,000 today if you agree to sell me this apartment at $300,000 anytime in the next 90 days, no matter how much it’s worth.”

You think: “Great! I get $5,000 just for agreeing to this. And I don’t think the neighborhood will boom anyway, so the buyer probably won’t exercise this deal.”

You agree and collect $5,000 immediately.

Three Scenarios

Scenario 1: Bad news – Neighborhood becomes isolated (stock falls to $250K)

- Your apartment is now worth $250,000

- The buyer says: “No thanks, I’m not exercising. This deal is worthless to me.”

- You keep: $5,000 premium (free money)

- Your profit: $5,000

- You still own the apartment worth $250K

Scenario 2: Great news – Neighborhood booms (stock rises to $400K)

- Your apartment is now worth $400,000

- The buyer exercises: “I’m taking your offer! Sell me the apartment at $300,000.”

- You’re forced to sell at $300,000

- You receive: $300,000 (your sale price) + $5,000 (premium you collected) = $305,000 total

- Your apartment is worth $400K, but you only got $305K

- You “missed” $95,000 in potential gains

- But you DID make $5,000 that you wouldn’t have made otherwise if you just held

Scenario 3: Moderate news – Someone else wants the rights (stock at $330K)

- The original buyer sees the neighborhood is improving slightly

- Another investor offers you: “I’ll pay you $10,000 for your obligation. I want to take over that deal.”

- You can accept: You pocket $10,000 total ($5,000 original + $5,000 new offer)

- The new buyer now has the right to buy at $300,000

- You’re out of the obligation

- Your profit: $10,000 without ever having to sell the apartment

Why Someone Would Sell a Call

Use Case 1: You own the apartment and want extra income

- You already own it at $300K

- You don’t think it’ll go above $350K soon

- You sell a call at $350K for $5K premium

- If it stays below $350K, you keep the apartment AND the $5K

- If it rises to $350K, you sell at your target price PLUS keep the $5K you earned waitingAnalogy that may fit you: It’s like renting the stock you own

Use Case 2: You don’t own it, but you think it won’t move

- You’re confident the neighborhood will stay stable

- You sell a call at $330K for $5K

- If it doesn’t rise to $330K, you pocket $5K with zero risk

- If it rises to $330K, you’re forced to buy at market price and sell at $330K (you lose money)

Let’s apply that way of looking at a trade on a chart: “if stock x is at $10 now,

- You own a stock, you entered at $8, you had enough of the profits

- Pick a price of $13 and give it time (30 days)

If it doesn’t reach that price, you keep the payment and the apartment.

If it does, you sell it for even more profit from stock rising plus you already received money for wanting to sell it at that price

Your full profit depends on what happens in the meantime, but you either:

- Get paid and keep the stock

- Get paid and sell stock for much more

- Get paid, stock falls a little – the money you got “negates that fall” a little

As an option buyer (holder), you pay a premium upfront.

As an option seller (writer), you collect the premium immediately.

Buying options gives you leverage with limited downside. You can control more of the underlying asset for less money. However, these options lose value over time.

Selling options generates income right away. Many sellers win more trades than buyers. These options have time on your side.

Your choice depends on your risk tolerance and market outlook. Buying works well for smaller accounts and beginners. Selling requires more capital and experience but can provide much more of a “steady income”.

Both strategies have their place in options trading. Understanding each side helps you make better decisions about which approach fits your goals.

As an option buyer (holder), you pay a premium upfront. You get the right to buy or sell the underlying asset at a set price. Your risk is limited to what you paid for the option.

As an option seller (writer), you collect the premium immediately. You must buy or sell the underlying asset if the buyer exercises their right. This strategy makes you honor the deal you got paid for receiving the premium and that can either be:

- Selling your stock at a certain price (sell a call – a strategy called covered call)

- Buying the asset at the price you said would buy at (sell a put – a strategy called cash secured put)

Risk and Reward Comparison:

| Position | Maximum Gain | Maximum Loss |

| Buy Call | Unlimited | Premium paid |

| Buy Put | Strike price minus premium | Premium paid |

| Sell Call | Premium received | Depends on how the stock moves |

| Sell Put | Premium received | Price of the underlying asset that you have to buy minus the premium you already received |

Buying options gives you leverage with limited downside. You can control more of the underlying asset for less money. However, these options lose value over time.

Selling options generates income right away. Many sellers win more trades than buyers. But when sellers lose, the losses can be much larger.

Your choice depends on your risk tolerance and market outlook. Buying works well for smaller accounts and beginners. Selling requires more capital and experience but can provide steadier income.

Both strategies have their place in options trading. Understanding each side helps you make better decisions about which approach fits your goals.

Buying vs Selling Options: Strategies & Risks

Types of Options

Options contracts give you the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an asset at a set price.

There are two types of options that everything else builds on:

CALLS and PUTS.

They then branch out to additional two types of positions which :

To SELL or to BUY the option.

Call options let you buy the underlying asset at the strike price.

If you buy a call, you’re hoping the asset’s price climbs above that strike before expiration.

If you sell a call, you’re most often hoping the asset’s price doesn’t reach that price.

Put options give you the right to sell at the strike price.

If you buy a put, you’re aiming for the price to drop below that level.

If you sell a put, you’re most often aiming for the price to not go below that level.

| Option Type | Right Granted | Market Outlook |

| Call Option | Right to buy | Bullish (expecting price increase) |

| Put Option | Right to sell | Bearish (expecting price decrease) |

Most stock options cover 100 shares per contract. It’s a lot of leverage for a relatively small amount of money.

The buyer pays a premium for this right and can choose to exercise or let the contract expire. Meanwhile, the seller gets the premium upfront but has to honor the contract if the buyer exercises.

Both calls and puts can be bought or sold, which gives you four basic positions: buying calls, selling calls, buying puts, and selling puts.

Option Terms to Know

If you want to trade options, you really need to know some key terms.

These basic definitions show up in almost every options strategy.

Premium is what you pay to buy the option.

That’s the most a buyer can lose.

Sellers get this as instant income.

Strike price is the agreed price where you can exercise the option.

Whether the option ends up valuable depends on how this compares to the market price.

The underlying is just the asset the option is based on—stocks, ETFs, indices, you name it.

Its price swings drive the option’s value.

Exercise means you use your right to buy or sell.

Call holders exercise to buy at the strike, put holders to sell.

Leverage lets you control big positions with less cash.

Options are famous for this, and it’s a big draw for many traders.

Margin is the collateral you need to sell options.

Spread strategies use more than one option at a time.

They can help you reduce risk or lower the cost of getting into a trade.

Liquidity is about how easily you can get in or out of an option.

More liquidity usually means tighter spreads and easier trades.

How to Buy Options

You need a brokerage account to buy options. Most online brokers will let you trade them, but you’ll need to get approved first.

Brokers will ask about your trading experience and risk tolerance.

Beginners usually start with basic approval, while advanced strategies need higher levels.

Steps to buy an option:

-

- Pick the underlying stock or asset

- Decide if you want to buy a call or put (which direction do you want to trade?)

- Choose your strike price that you think the asset will reach

- Check your breakeven price – this is the price at which you actually start earning on your trade

- Pick an expiration date – how much time you’re giving to the asset to reach that price and more

- Place your order and pay the premium

The premium is what you pay upfront when your order fills. That’s your total risk.

Things to check:

- Strike price – the price you can buy or sell at

- Breakeven price – to know when your trade actually gets profitable

- Expiration date – when the option ends

Optional:

- Volume – how much the option trades

- Bid-ask spread – the gap between buy and sell prices

When you buy an option, the most you can lose is what you paid.

If it expires worthless, that’s it—your premium is gone.

How do you close an options trade?

You can close your position early by selling the option back to the market.

This is good if you don’t have money to actually buy the stock and you earned money for being right about the direction of price.

Or, you can exercise it if you want the underlying asset.

What to look for when buying calls or buying puts?

For calls, you want the price to jump above the strike plus what you paid.

For puts, you want the price to fall below the strike price plus the premium you paid.

How to Sell Options

If you want to sell options, be aware that not every account qualifies—brokers have requirements and will check your experience.

Two main ways to sell options:

- Covered calls – Sell calls on stocks you already own.

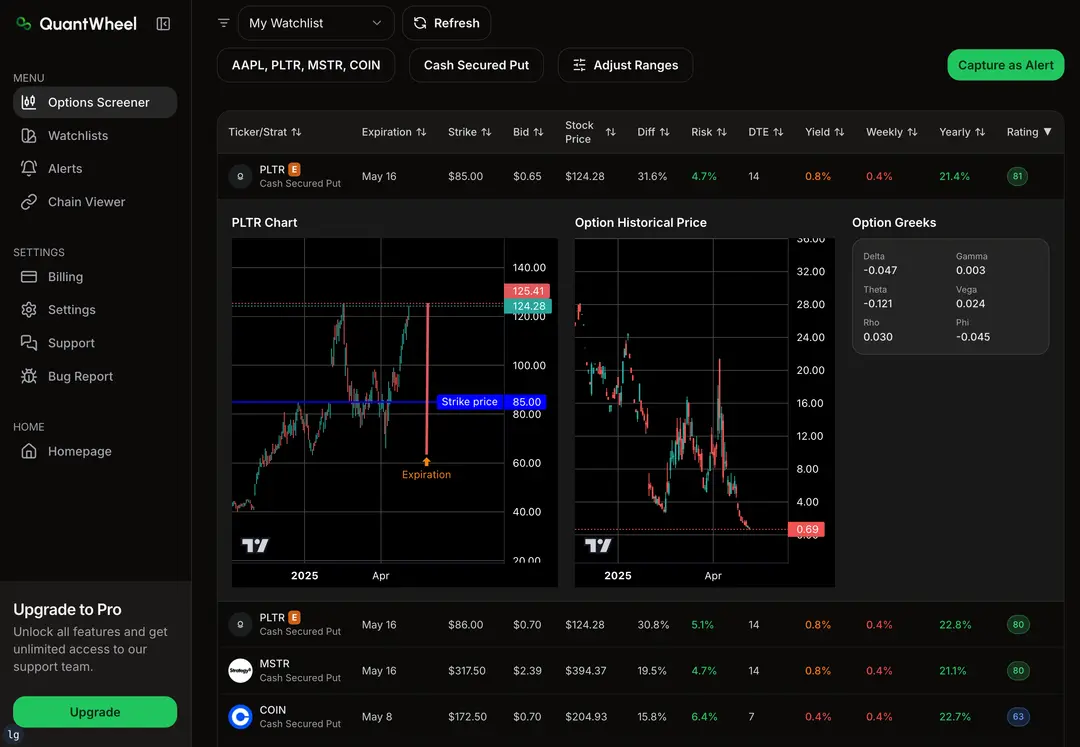

- Cash-secured puts – Sell puts with enough cash in your account to buy the stock if needed.

Depending on if you want to sell calls or sell puts:

If you sell a put – your account needs enough cash to cover possible stock buying.

If you sell a call – you have to own the stock already.

Getting Your Account Ready

Most brokers want you to have level 2 or higher options approval.

They’ll ask about your finances and trading background.

Sometimes, you’ll need at least $2,000 in your account to start selling options.

If you get the error where you can’t sell options on your account, this might be the issue.

Selling Process

- You pick the stock and strike price you want to sell.

- Find a “sell to open” order in your trading platform.

You’ll collect the premium right away.

This is the same for selling a call and selling a put, the only difference is where you pick the strike price.

Tips for selling calls and puts

For selling a call you typically pick a price that is currently higher than the stock.

For selling a put you typically pick a price that is currently lower than the stock.

How to sell an option step by step:

- Go to your stock and find “options chain”

- Set expiration

- Choose a strike price

- Find the sell call or sell put on either the left or right side

- Click order

- Select quantity

- Select order type (market)

- Receive the premium

Managing Your Trade

Keep an eye on your sold options every day. You can buy back the same contract to close out early—this is called “buy to close.”

It’s smart to set alerts for price moves. Many traders close out when they’ve made about 50% of the premium depending on the situation.

You can learn more about assignment later on in the course or jump straight to it here.

Buying Options: Common Strategies

Buying options gives you a few solid ways to try to profit from market moves.

Each one fits different conditions and risk appetites.

Call Options for Bullish Markets

Buy calls if you think prices will go up.

This gives you unlimited upside, but your loss is capped at what you paid.

For example, you might buy a call on XYZ stock with a $50 strike for $2.

If the stock jumps to $60, you’re in the money.

Put Options for Bearish Markets

Buy puts if you expect prices to drop.

You get the right to sell at a set price and profit as the stock falls.

For example, you might buy a put on XYZ stock with a $50 strike for $2.

If the stock falls to $40, you’re in the money.

What does In-the-money mean?

In short, it means you’re in profit.

Long Straddle

This one’s a bit more advanced and if you’re just starting out to learn options I recommend you to skip this one.

You buy both a call and a put on the same stock, same strike, same expiration.

If the stock moves big in either direction, you can make money.

Straddles work best when you’re expecting big news or volatility—think earnings reports.

Cool right? But don’t worry, we go more into detail and explain it simply here.

Timing Matters

Options lose value as expiration gets closer – at least if you buy them. What you need is quick, favorable moves for these strategies to really pay off.

Key Buying Strategies:

- Long calls – Bet on rising prices

- Long puts – Bet on falling prices

- Long straddles – Bet on big moves, any direction

- LEAPS – Longer-term options for more time

Your risk is always limited to the premium you paid.

This makes buying options attractive for smaller accounts or anyone wanting clear risk limits.

Selling Options: Strategies That Work

Selling options can help generate income and manage risk, but every approach has its own pros and cons.

Covered calls are great for investors who already own the stock. You sell calls against your shares, capping your upside but getting steady premium income.

This is just a fancy name for “sell a call” option trade.

Cash-secured puts let you collect premiums while maybe buying stocks at a discount. You need enough cash to buy 100 shares if assigned, though.

This is a fancy name for “sell a put” option trade.

Credit spreads involve selling one option and buying another at a different strike. This limits your risk and reward compared to selling naked options.

| Strategy | Risk Level | Income Potential | Capital Needed |

| Covered Calls | Low | Moderate | Stock + Margin |

| Cash-Secured Puts | Medium | Moderate | 100% Cash |

| Credit Spreads | Medium | Lower | Margin Only |

| Naked Options | High | Higher | High Margin |

Time decay is your friend as a seller. Options lose value every day, especially close to expiration, and you keep the premium if they expire worthless.

Still, managing risk is crucial. Use stop-losses and keep your position sizes reasonable, because things can move fast and losses can pile up.

Options Trading: Risks & Rewards

Options trading is a balancing act between potential gains and possible losses. Both buyers and sellers face different risks.

Risk Profiles

If you buy options, your risk is limited to the premium you paid. If the option expires worthless, that’s all you lose.

Selling options, though, can mean unlimited risk. If the market moves against you, losses can go way beyond the premium you collected.

Reward Potential

| Strategy | Max Gain | Max Loss |

| Buying Options | Unlimited | Premium paid |

| Selling Options | Premium received | Depends on the movement of a stock |

Buyers can see unlimited upside if the market moves just right. A small premium controls a big position, so the leverage can be wild. This is rare.

Sellers get paid upfront and hope the options expire worthless. If that happens, they keep the whole premium as profit. This occurs often.

Market Factors

Volatility plays a huge role in option prices. High volatility means higher premiums, which is nice for sellers but makes buying more expensive.

Time decay chips away at an option’s value each day. Buyers need the market to move fast, or the option loses value just from the clock ticking.

Using Options for Protection

Options can help you hedge against portfolio losses. They work a lot like insurance for your investments.

With a protective put, investors buy put options on stocks they own. If the stock price falls, the put option gains value while the stock is dropping and helps cover some of the loss with what you earned.

Covered calls are another way to hedge. Investors sell call options on stocks they already own.

This brings in extra income from the premium. It also cushions the loss if prices dip just a little.

In other words, if stock dropped 5%, you might have felt only the 3% fall.

| Hedging Strategy | Purpose |

| Protective Put | Protect against price drops |

| Covered Call | Generate income, minor protection |

Hedging with options usually costs less upfront than buying or selling the actual stocks. This is the advantage of options and why they are present.

Options hedging works best when you understand the specific risks you face. It’s important to match the strategy to your protection needs.

Some hedges defend against big losses. Others are more about steady income.

Hedging cuts down both possible losses and possible gains. You give up some upside to get more stability.

It’s a trade-off, but it can smooth out returns over time.

Taxes and Options Trading

Options trading has its own set of tax rules. The IRS treats buyers and sellers differently.

For Option Buyers:

If you buy calls or puts, you’ve got two choices: exercise the option or let it expire worthless.

If you buy a call or a put, you pay capital gains tax.

If you exercise a call and then sell the shares, you’ll pay capital gains tax. The rate depends on how long you hold the stock after exercising.

If you let the option expire, you can claim the premium paid as a capital loss. This is almost always a short-term loss, no matter how long you held it.

For Option Sellers:

Sellers get premiums upfront, but taxes work differently for them. If the buyer exercises your option, the seller pays tax on the proceeds.

When options expire worthless, sellers report the premium as a short-term capital gain. This applies even if they held the underlying stock for a while.

Special Cases:

| Contract Type | Tax Treatment |

| Stock options | Regular capital gains rules |

| Index options | 60/40 rule (60% long-term, 40% short-term) |

| Futures options | Section 1256 contracts |

Active traders might qualify for Trader Tax Status (TTS). This lets them deduct business expenses and avoid some limits on capital losses.

Good record keeping is critical for options traders. You need to track premiums, sales, and exercise dates to file taxes correctly.