Options Premium Basics

Options premium is what you pay to buy an options contract or receive if you sell an options contract.

It’s the cost for buyers and the income for sellers.

This premium has two parts: intrinsic value and extrinsic value.

These combine to make up the contract’s market price.

What Does Options Premium Mean?

The options premium is what a buyer pays upfront for an options contract.

Paying this premium gives the buyer the right—but not the obligation—to buy or sell an asset at a set strike price before expiration.

Sellers get the premium as income for taking on the contract’s obligation.

They keep this money whether or not the option gets exercised.

Basically, when buying a call or put you need to pay (premium).

When you sell a call or put you receive (premium).

That’s it.

Main Parts of the Premium:

- Market price of the contract

- Cost for buyers to get trading rights

- Income for sellers who write/sell the contract

How Options Premiums Move

Options premiums shift all day as markets change. The price reacts to the asset’s value, time left until expiration, and what people expect the price to do.

If a stock price jumps, call premiums usually rise and put premiums drop. If the stock falls, the opposite happens.

What Moves the Premium:

- Price changes in the asset

- Time decay as expiration gets closer

- Market volatility expectations

Buyers pay the premium upfront and risk losing it all if the option expires worthless.

Sellers pocket the premium but could “lose” much more if the market turns against them.

In terms of a trade going badly – the premium is the most a buyer can lose, for sellers, it offers a bit of a cushion against price drops.

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value

Options premiums break down into two pieces.

Intrinsic value is what you’d get if you exercised the option right now. Extrinsic value is tied to time and volatility.

Intrinsic value is the difference between the asset’s current price and the strike price, but only if that’s good for the option holder.

If it’s not in your favor, there’s no intrinsic value.

Calls have intrinsic value when the stock trades above the strike price.

Puts have it when the strike is higher than the stock price.

Extrinsic value covers time and implied volatility.

This part shrinks as expiration gets closer and disappears at expiration.

| Value Type | Description | At Expiration |

| Intrinsic | Immediate exercise value | Remains if in-the-money |

| Extrinsic | Time and volatility value | Becomes zero |

Options with more time left have more extrinsic value.

Higher volatility also boosts extrinsic value since it means more chances for big moves.

What influences options premiums?

Several things work together to set an option’s price. The asset’s market price is the base, but strike price and expiration matter a lot too.

How the Asset Price Matters

The asset’s price is the main driver for option prices.

When a stock goes up, call premiums rise since the odds of a profitability rise.

This applies if you just buy calls and if you sell calls (covered call strategy) too.

Puts move the other way.

If the stock climbs, put premiums drop since they’re less likely to end up in the money.

This applies if you just buy puts and if you sell puts (Cash secured put strategy) too.

Strike Price and Expiration

Strike price sets whether an option is in or out of the money.

When buying calls with lower strikes you need to pay more for them since they offer more profit potential.

That’s because the stock price is already “in and accounted for” to your trade and there’s less chance of it expiring worthless.

When buying puts —higher strikes cost more.

That’s because they cover more of the stock’s fall.

Expiration changes premiums by:

- Time decay – Options lose value as expiration nears

- Chance for movement – More time means more possible price swings

Options with only 30 days left lose value faster than those with 90 days. Time decay speeds up as expiration gets closer.

At-the-money options feel time decay the most. Deep in- or out-of-the-money options are less sensitive to time passing.

Volatility’s Role

Volatility is just the market’s guess about future price swings.

More volatility means higher premiums for both calls and puts, since big moves mean more opportunity.

Implied volatility is what the market expects.

Historical volatility is what actually happened.

Pricing models use implied volatility to help set premiums.

Volatility hits out-of-the-money options harder than in-the-money ones.

A small bump in implied volatility can boost an out-of-the-money premium a lot.

Events like earnings reports often send volatility—and premiums—soaring.

These periods benefit the sellers of option more because they get paid more to sell calls or sell puts.

Premiums in Trading and Investing

Option premiums are the backbone of options trading. They set the cost for buyers and the income for sellers.

Call and Put Premiums

Call premiums rise when the stock trades above the strike. If the market thinks the stock will go up, buying calls gets pricier and selling them gives you more income.

Put premiums go up when the stock drops below the strike.

Premium size depends on how “in the money” or “out of the money” the option is.

In-the-money options cost more because they already have value.

Out-of-the-money options are cheaper, but riskier.

Time eats away at both call and put premiums. Options lose value as expiration nears, especially in the final weeks.

Buyer and Seller Views

Buyers pay the premium upfront.

Their risk is capped—they can’t lose more than what they paid.

But they need the stock to move a lot to make money.

Sellers collect premiums instantly for taking on obligations. They keep the cash if the option expires worthless, but risk more.

Buyers need the stock to move past the strike price plus the premium. Sellers win if the option expires worthless or if they can buy it back cheaper.

Premium Strategies

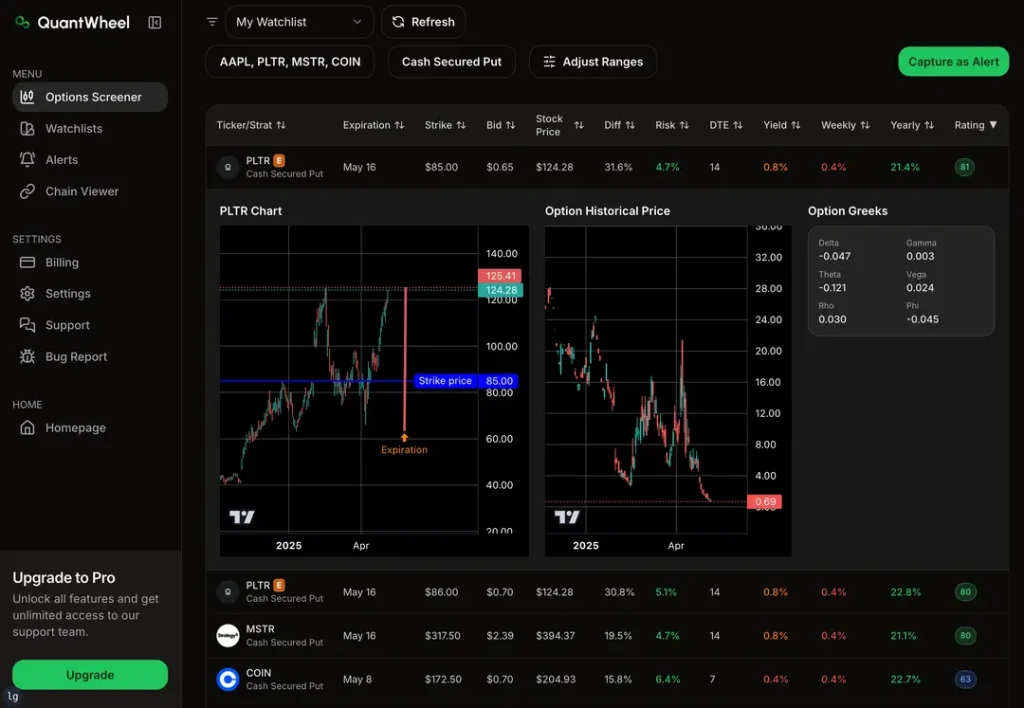

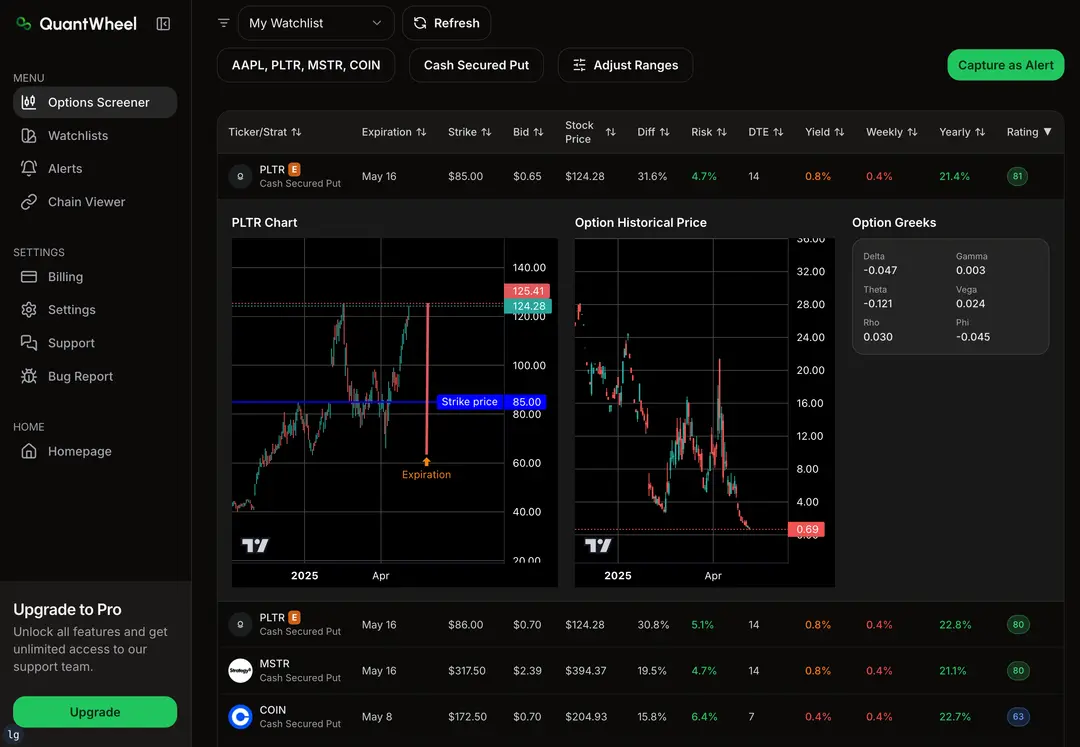

Income strategies focus on collecting premiums. Selling covered calls or cash-secured puts can bring in steady income.

Hedging uses premiums to protect your positions. Buying protective puts limits losses on stocks you own.

Speculation chases huge gains from small premium bets. Buying out-of-the-money options can pay off big—but it’s risky.

Spreads use a mix of buying and selling options to cut costs and cap risk. Bull calls and bear puts are popular choices.

Good options trading means knowing how premiums react to time, volatility, and the underlying stock. Planning around these changes and being flexible is key.